PRESIDENTE ZOD

Resultó que el Presidente Zod sabe que la libertad es la consecuencia del orden

Autor: Curtis Yarvin

Nota original: https://graymirror.substack.com/p/the-historical-guilt-of-the-old-regime

En inglés al pie.

Traducción: Hyspasia

Usualmente no respondo a ataques de los medios de masivos de prensa, o prensa legítima. Usualmente esos artículos provienen de la peor clase de cobardes, a los que Steve Sailer (el periodista más ilegítimo de los EEUU) denomina "señala y holgazanea". Nuestro héroe con tinta en las manos llega fumando, pone pose de intelectual, bebe algunos tragos y se las toma. Nuestro héroe no está acá para discutir y ciertamente no espero fuego cruzado. No sólo su texto es insignificante - ni siquiera vale la pena que se hable de él.

Mientras que en el caso de Matt McManus, que no es periodista pero al menos es un profesor - si bien un mero profesor adjunto, una modesta letrina, lejos de las gaviotas legítimas - las cuales escriben en Commoweal - aún así raramente católico, ha decidido cavar y hacer sus deberes. ¡O lo que cree son sus deberes! Mandaremos al Dr. McManus a su casa con más tarea para el hogar; ninguna obligación, y solamente lo elogiaremos si realmente decide hacerlo. Lo que no hará.

Debemos respetar a este hombre que ha decidido quedarse y averiguar. De todas formas, algunos otros deberán ser "incentivados" como dicen en Washington DC, para evitar tales malas decisiones en un futuro.

* * *

Déjenme empezar con una historia...

Los crímenes de nuestros abuelos

Es un hecho incontrovertible del SXX y de todas las tradiciones políticas del SXX, incluyendo la tradición norteamericana liberal y progresista, meterse en las políticas de aniquilación masiva. Y muchos todavía lo hacen - si es que ustedes los escuchan hablar sobre los rusos.

|

| Es absolutamente justo para mí pedir que todos los rusos y Rusia sean eliminados de la faz de la Tierra. No es solamente discurso de odio. No es discurso de odio, no es horrible para mí. Es simplemente JUSTO. |

¡Rusos! ¡Qué cosa extraña es la historia. Es el año 2023 y que los herederos de Pete Seeger griten nuevamente "Shriek with pleasur if we show / The weasel's tooth", aullando por armas y tanques y sangre en algún picadero de carne en Dnieper, tan deseosos ahora como cuando alguna vez cantaban por la paz y el amor y las flores - pero en contra de Rusia, de todos los países del mundo - es una de las más deliciosas ironías de la historia postmoderna. Y la más dolorsa. ¿Quién está bombardeando Donetsk?

Y aún así en el matadero ucraniano, tan absurdo como trágico, es una vuelta al pasado. En nuestro siglo los fuegos de los asesinatos masivos se han vuelto rescoldos - tal vez fruto de genuino avance espiritual, pero tal vez por una declinación general en la pasión y energía de la humanidad. Cuando la paz es sólo apatía, avaricia y azar, la paz no es síntoma de salud. La paz de la decadencia es la paz de la muerte.

Lo que es más peculiar de este hecho es que cuando pensamos sobre aniquilaciones masivas, pensamos en las campañas de aniquilación que ejecutan nuestros enemigos. Verdad: el holocausto puede haber sido el crimen mejor documentado en la historia humana. Pero es el crimen de ellos, no es nuestro crimen. Cuando vamos en búsqueda del espíritu redentor del pensamiento católico, o lo que sea, ¿estamos en el lugar correcto en términos morales cuando focalizamos en los crímenes de nuestros enemigos? Discutámoslo.

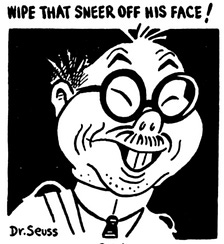

Verdad: No es nosotros y ellos. Es nuestros abuelos y sus abuelos - y la idea de un Sippenhaft nacional es una gigantesca hipocresía. Pero la historia todavía importa. Historia es poder, porque la narrativa es poder y porque el cuento del presente debe ser contado empezando por el pasado. Imaginen una Norteamérica en la cual todos los estudiantes iniciales de secundario tienen que sentarse toda la mañana a escuchar clases sobre "Hitler Vive", o leer Human Smoke de Nicholson Baker o tal vez la edición de Hiroshima de John Hersey impresa con las ilustraciones de Dr. Seuss:

Ningún relato del presente en la cual la Segunda Guerra Mundial sea una película de Marvel empezaría por semejante pasado. (Si usted tiene dudas de esto, debería pasar 15 minutos con "¡Hitler Vive!"). Y si la Segunda Guerra Mundial no es una película de Marvel - ¿cómo es que el presente tiene sentido?

Así las cosas, los padres de mi padre no participaron en borrar las sonrisas de las caras japonesas. Ni siquiera en cocinar las caras de ninguna niña japonesa en edad escolar. (¿Va usted a decir que si bien fue desafortunado fue necesario? Sólo escúchese a usted mismo). No - mi abuelo luchó en la Batalla de Bulge. Pero también, el era un norteamericano stalinista - desde 1930 hasta los '70.

Los bolcheviques también se unieron a este club de aniquilación en masa. Y aquellos que quieran interpretar el comunismo del SXX como infortunado pero esencial, la respuesta defensiva al fascismo del SXX tienen un problema de cronología que arreglar. Y lo mismo se puede decir para aquellos que interpretan la alianza entre los EEUU y la URSS como una reacción defensiva a Hitler. Hay mucho más en todo esto. Mucho más.

Volviendo al profesor McManus - que se presenta a sí mismo como progresista y socialdemócrata - cuando en el año 2023 usted lee la palabra "fascismo", una referencia a un movimiento de nuestros enemigos culturales derrotado hace 78 años, es un buen hábito reemplazar la palabra por "comunismo" en el documento - un movimiento de nuestros aliados culturales victorioso 78 años atrás - y preguntarse por qué es más importante estar temeroso de diablos muertos en lugar de diablos vivos.

Por supuesto que el partido de Lenin es literalmente el Partido Socialdemócrata Laborista. Y por supuesto que desde que Teddy Roosevelt fue a los grandes campos de caza en el Cielo - esto es por más o menos cien años - "progresista" en el discurso norteamericano significa exactamente "comunista". Mis abuelos, miembros del Partido Comunista de los EEUU (CPUSA) cuya fe nunca flaqueó, dijeron "progresistas" toda su vida; los despachos de Venona, los mensajes de la KGB por parte de activos en EEUU, usaban esa palabra ("progresista"). Que los niños estos días no tienen idea de lo que la palabra significa no los excusa. Y cierntamente no excusa al profesor de ciencias políticas - bueno, al menos adjunto. (Para ser justos, el joven McManus tiene un impresionante historial de publicaciones y seguramente seguirá en su camino hacia Harvard, siempre y cuando no use alguna palabra ilegal o le falte el respeto a alguna clase protegida).

Bernie Sanders, el abuelo favorito de todos los progresistas, pasó su luna de miel en la URSS. Imaginen si hubiera sido con Hitler. "Tomemos en consideración las fuerzas de ambos sistemas", dijo Charles LIndbergh luego de completar su viaje. "Aprendamos los unos de otros". A diferencia de las mentiras de los judíos, el viaje de Lindbergh no fue una luna de miel... no, meramente estableció una relación de "ciudad hermana" entre Saint Louis y la amorosa aldea alpina de Judenausrottung...

Ésta, para nosotros, los bebés de pañales rojos y nietos de la élite de la Ivy League, es la versión de lo que hoy los buenos alemanes llaman: Vergangenheitsbewältigung: hacer las paces con el pasado. Para no ser demasiado repetitivo - eso no quiere decir hacer las paces con el pasado del enemigo.

Por supuesto, la URSS de 1938 no era la misma que la URSS de 1988. ¿Hubiera sido el Tercer Reich de 1988 parecido al Tercer Reich de 1938? ¿España en 1968 era la misma que la España de 1968?

Y si la popularidad de la URSS en 1988, dentro de la clase más alta de la élite de la sociedad norteamericana, era una vela, la popularidad de la URSS en 1938, dentro de la misma élite norteamericana era una columna de alumbrado público. Un reflector en un estadio. No es una exageración afirmar que en los '30s, el "experimento soviético" era cool entre la gente cool.

El profesor McManus, también, es cool...aún si es "católico". De la misma manera. El también tiene que hacer-las-paces-con-el-pasado...si solamente hiciera su tarea para el hogar.

Libertad y Seguridad

McManus comienza sus burlas con una ponzoñosa cita a un escrito mío, claramente con la idea de shockear al lector:

|

| No hay razón en absoluto para un libertario, como yo, de no favorecer la ley marcial. Soy libre cuando mis derechos son definidos y asegurados en contra de cualquier contendiente, independientemente de sus pretensiones oficiales. Libertad implica ley; ley implica orden; orden implica paz; paz implica victoria. Como libertario, la mayor amenaza a la propiedad no es el Tío Sam, sino ladrones y forajidos. Si el Tío Sam se levanta de su presente sueño esclerótico y presenta a los forajidos una mano fuerte, mi libertad se ve incrementada. Curtis Yarvin, Carta Abierta a los Progresistas de Mente Abierta |

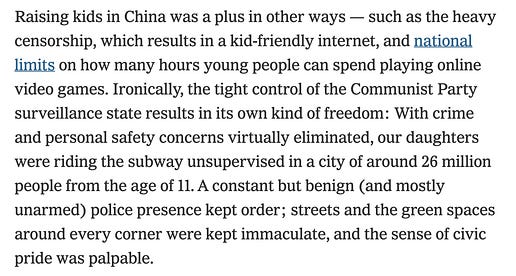

O como lo diría el New York Times - el otro día, en una operación de prensa coordinada, una norteamericana que cría sus hijos en China -

|

| Criar hijos en China tiene numerosas ventajas - como una fuerte censura, que resulta en una internet amistosa para niños y límites nacionales de cuántas horas la gente joven puede pasar on-line jugando videos. Irónicamente, el estricto control del Partido Comunista del estado resulta en su propia clase de libertad: Con el crimen y preocupación por la seguridad personal virtualmente eliminados, nuestras hijas de once años pueden andar solas en el subte sin supervisión, en una ciudad de 26 millones de habitantes. Un constante pero benigno (y mayormente desarmada) presencia policial cuida el orden; las calles y los espacios verdes son conservados inmaculados y el sentido de orgullo cívico es palpable. |

McManus se está burlando de está mujer. ¿Orgullo cívico? ¿Quién es? ¿Qué hizo esta mujer? No - él no tiene hijos - él tiene publicaciones - cualquiera puede tener hijos...

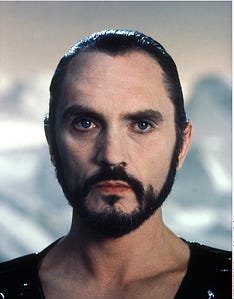

Tal vez entonces el deba tomárselas contra Ioan Grillo, el mejor narcoperiodista del planeta, quien recientemente escribió sobre el raro milagro de El Salvador...el cual, de alguna manera, sin que ninguno se diera cuenta, cayó bajo el control de un dictador libanés que se parece al General Zod sin tomar sol:

Resultó que el Presidente Zod sabe que la libertad es la consecuencia del orden. El Presidente Zod, con la simple política de construir gigantescas prisiones y llenándolas de todos monstruos tatuados que sus esbirros pueden encontrar, ha bajado la tasa de homicidios salvadoreña más que un orden de magnitud. La sacó de escala. Así es como los resultados son vividos en la calle:

|

| La situación ha cambiado radicalmente desde marzo, sin embargo, cuando el Presidente Nayib Bukele lanzó un brutal e imprecedente golpe sobre las bandas, incluyendo detenciones masivas. "Es una gran mejora" me cuenta Alas, explicando que las maras de su manzana han desaparecido. "Ahora podemos salir a la calle cuando queremos. Nuestra familia puede venir a visitarnos. Ningún presidente nos ha tenido en cuenta antes". |

¡Arrodíllense frente a Zod! Si "ahora podemos salir de casa cuando queremos" no es libertad ,¿qué es? Pero, ¿adivinen a quién le importa? No el presidente, pero:

|

| Los comentarios de Alas reflejan un apoyo amplio y generalizado por la ofensiva anti-bandas y por Bukele: un estudio de diciembre encontró que el 87,8% de los votantes encuestados lo apoyan, lo hacen el presidente más popular del continente, tal vez del mundo. Semejante popularidad contrasta ampliamente con el hostigamiento que le propinan a Bukele los grupos de derechos humanos, periodistas y miembros del Congreso de los EEUU. |

¿Demasiado colonialismo? ¿De qué lado está el profesor acá? ¿Colonialismo o democracia? Seguro que sus instintos le indican juntarse con "los grupos de derechos humanos, periodistas y miembros del Congreso de EEUU". Y no con la ama de casa salvadoreña.

Como McManus desdeñosamente repite mi posición:

Yarvin a veces escribe como si su problema con la izquierda democrática es que ésta está comprometida con el caos. Como el lo expone en su Gentle Introduction, "La derecha representa la paz, el orden y la segurida; la izquierda representa la guerra, la anarquía y el crimen". (Pregunta legal: ¿Es Bukele elegible para ser Presidente de San Francisco? "Fierro en guerra, oro en paz" [en castellano en el original], en efecto. Venga al norte [en castellano en el original] - tenemos tantos paisajes para mostrarle a usted...).

Ahora hablo como el hijo de un diplomático; digo que la élite global son genuinamente algunas de las mejores personas del mundo. Pero no siempre tienen razón. Y me desagrada bastante ver a miembros de mi propia casta caviar defendiéndonos a nosotros mientras simula defenderlos a ellos. En el mundo donde yo crecí, no hay pecado peor.

McManus escribe en un estilo impresionista, desprolijo, con insinuaciones sin base o evidencia, como:

En sus momentos más sinceros, Yarvin admitirá que sus verdaderas prioridades no son el orden y la estabilidad - al menos en el corto plazo - sino proteger la libertad de la élite al imponer estrictos controles a los órdenes inferiores de la sociedad.

¡Leyes estrictas para las órdenes inferiores! Semejante calumnia revela mucho sobre la extraña mente del progresista - enojado, como un leopardo acosado por su presa, que ha sido desafiado en su narcisista, psicótico y destructivo proyecto de imponer el caos en las "órdenes inferiores".

El caos, por supuesto, tiene una belleza en sí mismo. Me da pena reportar que esta belleza es desaprovechada - más que desaprovechada - en los "órdenes inferiores". Nunca es desaprovechada en la casta caviar - la cual, aunque el profesor McManus probablemente gane como U$D 39.000 al año, es un clase social. (Puede que él sólo haga como 29 mil - pero publica. Probablemente sea bien recibido en cualquier vernissage).

¿Cómo justifica McManus su posición? Si él tuviera que hablar con cualquier persona del común elegidas al azar tanto chinas como salvadoreñas que simplemente están contentos de sentirse seguros, y le explica a ellos por qué el Premier Xi y el Presidente Zod son, en realidad, malos, ¿Que diría él? Esto parece una oportunidad para un fascinante ensayo del profesor. Creo que ésta será nuestra primera muestra de tarea para el hogar.

Más mala historia

A medio camino en su ensayo, Mc Manus se va de sus devaneos y empieza a maltratarme por no encuadrarme en su ideologizada versión Chomskyte-Fonerite progresista de la historia del SXX. Creo que me compete contestarle con toda la compasión que pueda reunir en tal situación.

Siempre es conveniente darle al adversario el beneficio de la duda. Y en estos oscuros días aún el profesor de historia puede ser excusado por no saber que existe otra forma, además de esta inútil Nueva Izquierda, de leer el pasado. La historiografía es la madre de la historia, ¿y quién enseña historiografía? ¿O más aún, quién sabe qué es? Miremos parte del hueco y bilioso trabajo de McManus y tratemos de separar la paja del trigo.

Empieza de la mejor manera posible - me acusa a mí de no ser Chomskista.

Desprecia a C. Wright Mills y la aseveración de Noam Chomsky de que la riqueza conforma una élite política en los EEUU que no rinde cuentas a nadie. La verdadera élite que no rinde cuentas, sostiene Yarvin, consiste en Chomsky mismo.

¿Cómo que Chomsky no es élite? ¿A quién le rinde cuentas Chomsky? ¿A quién le rinde cuentas McManus? ¿Cómo es posible que él no sea de la élite? sólo por desarrollar un pensamiento literal sobre las palabras usadas, podemos aprender un montón.

Puedo explicar cómo los profesores universitarios son poderosos. ¿Cómo es la gente rica poderosa? Más aún, ¿Con "gente rica" nosotros nos referimos a "Mr. Burns" la caricatura de un republicano rico que se usa para un meme que se volvió rancio hace un siglo, o nos referimos a una clase de donantes que vuelva gigantescos ríos de dinero en ONGs progres? Si medimos el poder de los ricos por el valor político de sus donaciones, vemos claramente que el progresismo en sí mismo es una medida del poder del dinero en el régimen norteamericano. ¿Ha el profesor McManus realmente alguna vez escuchado de la Fundación Ford? ¿Orly? El poder no va en contra del profesor - está de su lado. (Chomsky mismo es un viejo raro, si bien su influencia indirecta - como vemos - permanece absurdamente inmensa).

En busca de argumentos coherente en el texto de McManus llegamos a otra cita a mi trabajo al que él caracteriza de "simplemente bizarra":

Es un hecho muy difícil de discutir que la Guerra de Secesión [su término para la Guerra Civil de EEUU - McManus] hace la vida de cada uno más placentera, incluyendo la de los esclavos liberados. (Tal vez el mejor ejemplo sería los neoyorkinos que sacaron provecho y los poetas de la unión que escrbieron homilías de guerra). La guerra destruyó la economía del Sur. Trajo pobreza, enfermedades y muerte.

McManus responde:

Yarvin no menciona que también trajo la emancipación y algún grado de justicia, a pesar de los esfuerzos de los supremacistas blancas de reinstaurar su poder a través de la violencia y los esfuerzos contra el sufragio universal.

Quiero focalizar la atención, querido lector, en sus visiones que se contraponen entre sí - un conflicto de costos que son concretos, como "pobreza, enfermedades y muerte" y los beneficios que son abstractos como "emancipación y algún grado de justicia".

Nosotros los de la casta caviar somos muy buenos con las abstracciones. Yo amo las abstracciones. Me ayudan a pensar. Aún así, cuando el precio de una abstracción, como "emancipación y justicia" es muy alto, como "pobreza, enfermedades y muerte", tal vez empezaría con la pregunta de qué es lo que estoy comprando. No parece ser un tema para profesor McManus - cuya desaprensión en esta materia es escalofriante.

Su tarea aquí es leer 10 o (mejor) 20 narraciones elegidas al azar de esclavos. En un increíble y épico acto de fabricación de empleo para historiadores desempleados, el Proyecto de Escritores Federal en la década de 1930 buscó tantos ex-esclavos como pudo encontrar y les tomó sus historias en forma oral y la llevaron al papel. Entonces, ahora en el SXXI, si usted quiere comparar la vida de un esclavo al azar en 1855 con la vida de un peón rural - también elegido al azar - en 1875, no tiene necesidad de preguntarle nada a un desperdicio de oxígeno de marxista de Brooklyn. Se lo puede preguntar a un esclavo. Inténtelo.

Usted debe haberse hecho preguntas incómodas como: "¿La Segunda Guerra Mundial fue buena para los judíos?" McManus parece un nombre irlandés - ¿los Troubles, fueron buenos para los irlandeses? ¿Es mejor ser gobernado por Bruselas que por Londres? "Son sólo preguntas, León".

Dicho sea de paso "la Guerra de Secesión" es el nombre europeo para la guerra y lo prefiero porque no es un nombre que genere controversia - como los nombres usados por el Norte o por el Sur. El trabajo de un historiador es imaginar qué es lo que realmente sucedió, no golpear a los enemigos políticos en la cabeza con propaganda tendenciosa, emocional y juvenil. De nuevo, en 2023, es fácil por qué alguno puede tener esa impresión.

...

Conclusión

Alas, después de esta divertida disgresión en una historia que si bien mentirosa, McManus recobra su estilo lleno de clichés:

Volviendo el foco a los errores del pensamiento de Yarvin uno es perder el punto del que se trata. Lo que lo hace tan atractivo a tantos miembros de la derecha no es la calidad de su razonamiento sino su indisputable habilidad de expresar el resentimiento reaccionario con un vocabulario tecnohipster del SXXI. El resentimiento de la extrema derecha combina la actitud de victimizarse con sentimientos megalomaníacos de superioridad personal. Toma la forma de insistir que se pertenece a una élite natura que merece status y poder. Mucho de la tradición reaccionaria es una larga serie de "gestos mentales irritables [sic]" en respuesta a hechos indignantes que, de alguna forma, los claramente inferiores siguen ganando el partido. Esto es usualmente seguido de tediosas instrucciones de como los naturalmente superiores puede "retomar" el poder.

Por "claramente inferior" entiendo que McManus no se refiere a sí mismo ni a su clase caviar, a sus amigos que ven NPR, sino a los haitianos, a los trabajadores, a los comunes, a los proletarios, etc. a quien McManus dedica sus fatigas de dar clases por poca paga en su mina de sal académica con su eterna provisión de agua fresca.

Después de un tiempo la amarga experiencia de un siervo de la academia y de un siervo agrícola se confunden - el profesor adjunto es una especie de aparcero, pagado con un manojo de peniques y restringido a un paisaje triste de llanura aluvional del posmodernismo chomskiano-fonerista. No hay biodiversidad en la granja de tierra roja. Hay una única cosecha. McManus no tiene alternativa que recolectarlar. Imagínenlo estando de acuerdo conmigo, luego intentando hacer carrera. Aún con todo su record de publicaciones, tendría suerte si sale vivo de Michigan. ¡Triste! La paz empieza al sentir el dolor de tu enemigo.

* * *

|

The historical guilt of the old regime

"Presidente Zod, it turns out, knows that freedom follows order."

I don’t usually respond to attacks from the mainstream, or as I prefer legitimate, press. Usually these articles are of the craven drive-by type that Steve Sailer (America’s best illegitimate journalist) calls “point and sputter.” Our ink-stained hero comes smoking in, screeches to an intellectual “California stop,” sprays a few rounds, and peels out. Our hero is not here to engage and is certainly not expecting any variety of return fire. Not only is his text worthless—it is not even worth taking to task.

Whereas one Matt McManus, no journalist but at least a professor—if a mere lecturer, a humble grove-toiler far from the seagull’s cry—writing in Commonweal—legitimate, yet still oddly Catholic—has bravely chosen to dig in and do his homework. Or what he thinks is his homework! We’ll send Dr. McManus home with more homework; no obligation, and only praise if he actually decides to do it. Which he won’t.

We have to respect this one OG who decided to stick around and find out. However, others should be “incented,” as they say in DC, to avoid similar bad choices in future.

Let’s start with some history…

The crimes of grandfathers

It is an incontrovertible fact about the 20th century that all 20th-century political traditions, including the American liberal and progressive tradition, traded in the politics of mass annihilation. As many still do—if you hear them talk about Russians.

Russians! How strange a thing is history. It’s 2023, and that the heirs of Pete Seeger should again “Shriek with pleasure if we show / The weasel’s tooth,” baying for guns and tanks and blood in some Dnieper meatgrinder, as eagerly as they once sang for peace and love and flowers—but against Russia of all countries—is the most delicious of history’s postmodern ironies. And the most painful. Who is shelling Donetsk?

And yet the Ukrainian abattoir, as absurd as it is tragic, is a throwback. In our century the fires of mass slaughter have burned low—perhaps from genuine spiritual advance, but perhaps from a general decline in the passion and energy of humanity. When peace is just apathy, avarice and accidie, peace is not a symptom of health. The peace of decline is the peace of death.

What is most peculiar about this fact is that when we think about mass annihilation, we think about our enemies’ campaigns of mass annihilation. True: the Holocaust may be the best-documented crime in human history. But it is their crime, not our crime. When we go looking for the spirit of redemptive Catholic thinking, or whatever, are we in the right moral place when we focus on the crimes of our enemies? Discuss.

True: it is not us and them. It is our grandfathers and their grandfathers—and the idea of a national Sippenhaft is itself a gross hypocrisy. But history still matters. History is power, because narrative is power, and because the story of the present has to be told by starting from the past. Imagine an America in which every high-school junior had to sit through Hitler Lives before lunch, or read Nicholson Baker’s Human Smoke, or maybe an edition of John Hersey’s Hiroshima printed with Dr. Seuss’s war cartoons:

No history of the present in which World War II was a Marvel movie could start from any such past. (If you doubt this, you really should spend 15 minutes with Hitler Lives!) And if World War II was not a Marvel movie—how does the present even make sense?

As it happens, my own father’s parents did not participate in wiping the bucktoothed smiles off any Japanese faces. Or even cooking the faces off any Japanese schoolgirls. (Were you going to say this was necessary, though unfortunate? Just listen to yourself.) No—my grandfather fought in the Battle of the Bulge. But also, he was an American Stalinist—from the 1930s to the 1970s.

The Bolsheviks too joined the “two-comma club” in mass murder. And those who want to interpret 20th-century communism as an unfortunate, but somehow essential, defensive response to 20th-century fascism have a chronology problem to finesse. And the same is true of those who want to interpret the alliance between the US and USSR as a defensive reaction to Hitler—more on this anon. Much more.

Returning to Professor McManus—a self-described progressive and social democrat—when in the year 2023 you read the word “fascism,” a reference to a movement of our cultural enemies that was defeated 78 years ago, it is a good habit to ^F the document for “communism”—a movement of our cultural allies that was victorious 78 years ago—and wonder why it is more important to be afraid of dead devils, than living ones.

Of course Lenin’s party was literally the Social Democratic Labor Party. And of course since Teddy Roosevelt went to the great hunting grounds in the sky—that is, for about the last century—“progressive” in American discourse has just meant “communist.” My grandparents, CPUSA members whose faith never lapsed, said “progressive” for their whole lives; the Venona dispatches, messages to the KGB from US assets, use it. That kids these days have no idea what this word means does not excuse them. And it certainly does not excuse a political-science professor—or, at least, lecturer. (To be fair, young McManus has an impressive publishing record and is surely well on his way to Harvard, so long as he doesn’t use an illegal word or disrespect a protected class.)

Bernie Sanders, everyone’s favorite progressive grandpa, “honeymooned” in the USSR. Imagine if it was Hitler. “Let’s take the strengths of both systems,” Charles Lindbergh said upon completing his trip. “Let’s learn from each other.” Contrary to Jewish lies, Lindbergh’s journey was not a honeymoon… no, he was merely establishing a “sister city” relationship between St. Louis and the lovely Alpine village of Judenausrottung…

This, for we red-diaper babies and grandbabies of the Ivy League elite, is our version of what today’s good Germans call Vergangenheitsbewältigung: coming to terms with the past. Not to be overly repetitive—but that ain’t supposed to mean your enemy’s past.

Of course, the USSR of 1938 was not the USSR of 1988. Would the Third Reich of 1988 have been the Third Reich of 1938? Was the Spain of 1968 the Spain of 1938?

And if the popularity of the USSR in 1988, among the most elite American social class, was a candle, the popularity of the USSR in 1938, among the most elite American social class, would be a streetlight. A stadium light. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that in the 1930s, the “Soviet experiment” was cool among all cool people.

Professor McManus, too, is cool… even if he is a “Catholic.” In the same way. He has some coming-to-terms-with-the-past to do—if he will only do his homework.

Liberty and security

McManus starts his sneering screed with an old quote of me, clearly meant to shock:

Or as the New York Times put it—just the other day, in an op-ed by an American who had raised her children in China—

McManus is already sneering at this woman. Civic pride? Who is this? What has she done? No—he doesn’t have children—he has publications—anyone can have children…

Maybe then he should take it up with Ioan Grillo, the planet’s top narco-journalist, who recently wrote about the weird miracle of El Salvador… which has somehow, without anyone noticing, fallen under the control of a Lebanese dictator who looks like General Zod with a tan:

Presidente Zod, it turns out, knows that freedom follows order. Presidente Zod, by the simple policy of building gigantic prisons and filling them with all the tattooed monsters his jackbooted minions can find, has brought the Salvadoran homicide rate down by more than an order of magnitude. This is how the result looks on the street:

Kneel before Zod! If “now we can go outside when we like” isn’t freedom—what is? But guess who really cares—not the Presidente, but:

Colonialism much? Which side is the Professor on here—democracy, or colonialism? It sure seems like his instinct would be to go with the “human rights groups, journalists, and members of the US Congress.” And not the Salvadoran housewife.

As McManus himself scornfully reprises my position:

Yarvin sometimes writes as if his problem with the democratic Left is that it is committed to chaos. As he puts it in Gentle Introduction, “Right represents peace, order and security; left represents war, anarchy and crime.”

Indeed, and you have no further to look than Presidente Zod versus the human-rights groups to see what I meant. (Legal question: is Bukele eligible to be Presidente of San Francisco? “Fierro en guerra, oro en paz,” indeed. Venga al norte—we have such sights to show you…)

Speaking as a diplomat’s son, I will say that the global elite are genuinely some of the best people in the world. But we are not always right. And it rather displeases me to see a member of my own caviar caste sticking up for us, while he pretends to be sticking up for them. In the world I grew up in, there is no worse sin.

McManus writes in this smeary impressionistic point-and-sputter style that will toss off, absolutely without any basis or evidence, huge sweeping insinuations like

In his more candid moments, Yarvin will admit that his real priorities aren’t order and stability—at least in the near term—but protecting the freedom of an elite by imposing strict laws on the lower orders.

Strict laws on the lower orders! Such slurs reveal so much about the weird progressive mind—angry, like a leopard accosted at its prey, that it has even been challenged in its narcissistic, psychotic and destructive project of imposing chaos on the “lower orders.”

Chaos, of course, has a beauty of its own. I am sad to report that this beauty is wasted—more than wasted—on the “lower orders.” It is never wasted on the caviar caste—which, though Professor McManus probably makes like 39K, is a social class. (He may only make 29K—but he has publications. He is surely welcome at anyone’s art opening.)

How does McManus justify his position? If he had to talk to random ordinary Chinese and Salvadoran people who just like being safe, and explain to them why Premier Xi and Presidente Zod are, actually, bad, what would he say? This seems like a chance for a fascinating essay from the Professor. I think it’s our first piece of homework.

More bad history

About halfway through his essay, McManus runs out of point-and-sputter and starts just wildly smearing me for not conforming to his wildly ideological Chomskyite-Fonerite progressive history of the 20th century. I feel it’s incumbent on me to respond with as much compassion as I can muster under the situation.

It is always good to give an adversary the benefit of the doubt. And in these dark days even a history professor can be excused for not knowing that there is any other way, besides this worthless New Left mouthbreathing, to read the past. Historiography is the mother of history, and who teaches historiography? Or even knows what it is? Let’s work through some of McManus’ shallow, bilious spittle and try to sort it out.

He starts this run in the best possible way—by accusing me of not being a Chomskyite:

He dismisses C. Wright Mills and Noam Chomsky’s claim that the wealthy constitute an unaccountable political elite in the United States. The real unaccountable elite, Yarvin claims, consists of people like Chomsky himself.

How is Chomsky not elite? Who is he accountable to? Who is McManus accountable to? How is he not elite? Just by thinking logically in literal words, we can learn a lot.

I can explain how professors are powerful. How are rich people powerful? Moreover, which rich people do we mean—the “Mr. Burns” Republican caricatured rich people who are a meme that has been stale for a century, or the actual social donor class that pours giant rivers of money into progressive NGOs? If we measure the power of the rich by the political valence of their donations, we see clearly that progressivism itself is a measure of the power of money in the American regime. Has Professor McManus really never heard of the Ford Foundation? O rly? That power is not set against the professors—it is very much on their side. (Chomsky himself is an old weirdo, though his indirect influence—as we see—remains absurdly immense.)

Wading through McManus text for a coherent argument which is more than a sneer, we reach another quote of mine which he calls “simply bizarre":

It is in fact very difficult to argue that the War of Secession [his term for the American Civil War—McManus] made anyone’s life more pleasant, including that of the freed slaves. (Perhaps your best case would be for New York profiteers and Unitarian poets who produced homilies to war.) War destroyed the economy of the South. It brought poverty, disease and death.

Success has destroyed Substack and made it impossible to enter a nested blockquote. McManus responds:

He does not mention that it also brought emancipation and some measure of justice, despite the efforts of white supremacists to reassert their power through violence and anti-suffrage efforts.

I want to focus your attention, dear reader, on this conflict of visions—a conflict of costs that are concrete, like “poverty, disease and death,” and benefits that are abstract, like “emancipation and some measure of justice.”

We in the caviar caste are very big on abstractions. I like abstractions. They help me think. However, when the price of an abstraction, like “emancipation and justice,” is very high, like “poverty, disease and death,” I might start to question what I was buying. This does not appear to be an issue for Professor McManus—whose carelessness in this matter is chilling.

His homework here is to read 10 or (better) 20 randomly chosen slave narratives. In an incredibly epic act of makework for unemployed historians, the Federal Writers Project in the 1930s rounded up as many living ex-slaves as they could find and took their oral histories. So, in the 21st century, if you want to compare the life of a random slave in 1855 with the life of a random sharecropper in 1875, you have no need to ask some mouthbreathing Brooklyn Marxist. You can ask a random slave. Try it.

You may have already asked yourself similar troubling questions, like: “World War II, was it good for the Jews?” McManus sounds like an Irish name—the Troubles, were they good for the Irish? Is it way better to be ruled from Brussels, than from London? “They’re just questions, Leon.”

By the way, “War of Secession” is the European name for the war and I like it the best, because it is not a name that makes an argument—unlike the Northern or Southern names. The job of a historian is to figure out what really happened, not to beat his political enemies over the head with tendentious, emotional, juvenile propaganda. Again, though—in 2023, it’s easy to see why someone might get that impression.

Then there are the many places where Yarvin insists that the United States, from Wilson onward, handled Communism with a velvet glove. He simply dismisses the fact that Wilson sent soldiers in to crush the Bolshevik Revolution…

The Cold War is unfortunately one area in which progressive historiography is so universal that there is almost no systematic scholarship that is worth a barrel of piss. A good rule of thumb is that if your historiography of the Soviet Union matches the Soviets’ own historiography, some long-forgotten communist has urinated in your tea. This whole subplot needs to be totally revised and it’s not like there is money to do it.

The axiomatic assumption of almost all academic students of the Cold War is that there was no good reason for these revolutionary progressive powers to quarrel, and every reason for their revolutions to converge. From this starting point, they look for “hardliners” on each side who fomented this unnecessary animosity. The question of why so many fine Americans of the caviar caste were funding, protecting, and collaborating with this gigantic gang of mass murderers is seldom if ever raised.

Professor McManus’ homework is to read Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution, by Antony Sutton—by no means a perfect historian, but a brave one—America’s Siberian Adventure, by William Graves, commander of the Siberian intervention, which will leave him embarrassed (if the Professor is capable of embarrassment) about his appalling Leninist lie of “sent soldiers in to crush”; Raymond Robins’ Own Story, a shameless hagiography of Raymond Robins, leader of the Red Cross Mission which was an informal American embassy to the Bolsheviks, and Russia From the American Embassy, by David Francis, the official US ambassador to the Kerensky regime.

While this is a long assignment, it is a deeply rewarding journey into historiography. Among the interesting things the reader will see is the way that Graves and Robins virulently deny being on the Bolshevik side, while in fact all their objective actions favor the Bolshevik party line. Robins’ hagiographer writes of him:

He is the most anti-Bolshevik person I have ever known, in way of thought; and I have known him for seventeen years. When he says now that in his judgment the economic system of Bolshevism is morally unsound and industrially unworkable, he says only what I have heard him say in every year of our acquaintance since 1902.

This is a peculiar thing to say in a book that starts with:

With Bolshevism triumphant at Budapest and at Munich, and with a Council of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Deputies in session at Berlin, Raymond Robins began to narrate to me his personal experiences and his observations of the dealings of the American government with Bolshevism at Petrograd and at Moscow.

But he was not merely an observer of those dealings. He was a participant in them. Month after month he acted as the unofficial representative of the American ambassador to Russia [sic—actually, he was the ambassador’s principal enemy] in conversations and negotiations with the government of Lenin. Throughout that period he saw Lenin personally three times (on average) per week [my italics].

All sources, including this book, agree that Robins was the chief American emissary to, and American promoter, of the Bolsheviks in this period. The Robins party line is that the Bolsheviks are bad, but we have to be realists and “deal” with them. This facile excuse, with its “pinprick” attack to demonstrate mandatory hostility to the Bolshevik beast, feels theatrical and perfunctory. It is found in many works of the period.

Pitirim Sorokin, a young Russian politician who fled the Revolution and became a prominent American sociologist, sees Robins in action in Moscow:

The despotic nature of the Bolsheviks’ policy became daily more apparent. After having broken up the Constitutional Assembly, while the autocratically appointed (not elected) All-Russian Conference of the Soviets held their meeting in Moscow, a meeting in which the American Red Cross Colonel, Raymond Robins, actively participated, while they were welcoming the “Power of the Peasants and Workers,” they began to break up all newly elected Soviets which in any degree resisted their tyranny…

Antony Sutton quotes a seized document:

On returning to the United States in 1918, Robins continued his efforts in behalf of the Bolsheviks. When the files of the Soviet Bureau were seized by the Lusk Committee, it was found that Robins had had “considerable correspondence” with Ludwig Martens and other members of the bureau.

One of the more interesting documents seized was a letter from Santeri Nuorteva (alias Alexander Nyberg), the first Soviet representative in the U.S., to “Comrade Cahan,” editor of the New York Daily Forward. The letter called on the party faithful to prepare the way for Raymond Robins:

Dear Comrade Cahan: It is of the utmost importance that the Socialist press set up a clamor immediately that Col. Raymond Robins, who has just returned from Russia at the head of the Red Cross Mission, should be heard from in a public report to the American people. The armed intervention danger has greatly increased. The reactionists are using the Czecho-Slovak adventure to bring about invasion. Robins has all the facts about this and about the situation in Russia generally. He takes our point of view.

In other words, like Wilson and other American progressives of the period, he ran all the interference he could for the nascent—and already bloodthirsty—USSR. From the first, Lenin and Wilson both played the Raymond Robins game of vociferously and hyperbolically and hypocritically denouncing each other. They were always genuinely competing—and they genuinely wanted to obscure their genuine collaboration.

When we dig deeply enough into history to actually figure out what really happened, not just to find facile stories to beat our enemies over the heads with, we have no choice but to grapple with these attempts at obscuring, these “set-up clamors.” Is figuring out the present easy? Sincerely figuring out the past is much, much harder.

…and jailed members of America’s socialist party.

Debs was in no way working with or associated with Lenin—though they certainly had many supporters in common.

And in case Professor McManus has somehow not noticed, vicious, often bloodthirsty factional infighting has been the hallmark of all 20th-century leftist movements. It is also true that Hitler jailed Roehm and sidelined Strasser. We do not conclude from this that the solution to radical Nazi terrorism is to support moderate Nazis.

But the best of these little tussles with the 21st-century academic consensus is over the beautiful island country of Haiti. In the 19th century, Haiti was the only part of the world that had fallen to the chaotic Third World conditions which, after 1950, became common in the former European colonies. So by reading 19th-century reactions to Haiti, we can see how the 19th century would have regarded the 20th—or at least, one important aspect of the 20th.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, I wrote:

In Haiti, we see one aspect of life without promises made and kept: poverty, corruption, violence and filth. In a word: anarchy. Haiti is the product of the persistence of human anarchy, and an excellent symbol because it symbolized exactly the same thing to Carlyle and Froude. The latter visited; his observations are recorded in his travelogue of the trip, The English in the West Indies; Or, the Bow of Ulysses. Haiti is far more anarchic now than it was in 1888, of course, whose Port-au-Prince is a paradise next to today’s. Froude gets all enraged because he sees a ditch full of garbage. The 19th century’s Haiti is the 21st’s whole Third World.

McManus is not amused:

All of this is wildly misleading. Haiti was founded by heroic men and women who launched the first successful slave revolt in history.

It is amazing how even the tone of the narrative, with words like “heroic,” has become as factual as the date of a battle to this sorry excuse for a scholar. Haiti was founded by heroic men and women who launched—well, not the first—revolutionary genocide in history. As Wikipedia dryly notes:

The Haitian Revolution defeated the French army in November 1803 and the Haitian Declaration of Independence happened on January 1st 1804. From February 1804 until 22 April 1804, squads of soldiers moved from house to house throughout Haiti, torturing and killing entire families. Between 3,000 and 5,000 people were killed.

Not to worry! “Torturing and killing entire families” can be good akshually:

Nicholas Robins, Adam Jones, and Dirk Moses theorize that the executions were a “genocide of the subaltern,” in which an oppressed group uses genocidal means to destroy its oppressors.

20th-century scholarship! Never change. (Don’t worry, it won’t.) The explanations for Haiti’s failure to be Japan have shifted over the years—I feel I reached a real low this summer, when a progressive I was debating on stage insisted that what Haiti really needs, to start turning itself into Japan, is a higher minimum wage:

As a monarchist, I can tell you that Haiti could probably use Emperor Jacques back, genocide or no genocide, since it currently has no elected officials and is under the de facto control of a gang leader known as “Barbecue”—whose Wikipedia page notes:

Chérizier has denied that his nickname “Babekyou” (or “Barbecue”) came from accusations of his setting people on fire. Instead, he says it was from his mother's having been a fried chicken street vendor.

¿Porque no los dos? But the latest Haiti just-so story to grace the pages of the narrative, incredible as its chutzpah may seem, is that Haiti in 2023 looks like the above because of—the indemnity that the French made them pay for the aforesaid genocide—almost 200 years ago.

After several unsuccessful efforts to take back the island by force, the French King Charles X ordered the Haitians to pay upwards of 40 percent of their national income to former slaveholders in reparations or face further violence. Thomas Piketty estimates that the French owe the Haitians at least $28 billion from this extortion.

Professor McManus’s views, or Piketty’s for that matter, on the Treaty of Versailles, were not recorded. The Third World’s history of unpayable national debt is a long one. The world’s history of unpayable national debt is a long one.

However, if we humor the ridiculous Marxist theory that the First World has kept the Third backward through profitable extraction of colonial rents, debt payments, etc, we have to at least keep ourselves grounded by measuring the actual net payments—rather than notional amounts which not only could not be paid, but were not paid. The notional amounts in the Treaty of Versailles were pretty high, too—to say nothing of a certain indemnity to Israel—and yet Bavaria, apparently, is doing fine. It certainly doesn’t look much like the photo above.

Helpfully, Wikipedia, which is a reliable source, has this number—sourced, I believe, from the New York Times:

Over a period of about seventy years, Haiti paid 112 million francs to France, about $560 million in 2022.

These were payments on the gold standard. A French gold franc is 0.29 grams of gold; a gold dollar was 1.6 grams of gold; so this was about 20 million dollars in gold, over 70 years. 30x price inflation since the 19th century is a good rule of thumb, so $560M feels about right. (Larger numbers seem to include interest.) When I work this out in gold inflation rather than by price inflation, I get about $2B.

For a country… over 70 years… this is not a lot. Is this 19th-century debt really why Haiti does not look like Bavaria? Is Professor McManus sure about that? Are there really no other countries that had a lot of 19th-century foreign debt, yet prospered? His homework is to read The French Revolution in San Domingo, by Lothrop Stoddard, and Where Black Rules White, by Hesketh Pritchard.

Conclusion

Alas, after this fun digression into actual if mendacious history, McManus gets back into his mode of stale, windy revolutionary cliches:

But to focus on the flaws in Yarvin’s thinking is to miss the point. What has made him appealing to so many on the Right isn’t the quality of his reasoning but his undeniable ability to express reactionary ressentiment in a twenty-first-century techno-hipster vocabulary. Right-wing ressentiment combines a similar attitude of victimhood with megalomaniacal feelings of personal superiority. It takes the form of insisting that one is part of some natural elite that deserves status and power, but is persecuted by the weak and inferior who dare to demand equal status with the strong. Much of the reactionary tradition is a long series of “irritiable [sic] mental gestures” in response to the outrageous fact that, somehow, the clearly inferior keep gaining the upper hand. This is usually followed by tedious instructions on how the naturally superior can take power “back.”

By “the clearly inferior,” I take it McManus does not mean himself and his caviar-class, NPR-listening friends—but the Haitians, workers, peasants, etc, on whose behalf he toils, lecturing for far too little pay, in the academic saltmine of a freshwater college.

Over time, the grim experience of an academic serf and that of an agricultural serf seem to merge—the lecturer is a sort of sharecropper, paid with a handful of pennies, and restricted to the grim floodplain landscape of postmodern Chomsky-Fonerism. There is no biodiversity on this red-dirt farm. There is only one crop. McManus has no choice but to pick it. Imagine him agreeing with me, then trying to have a career. Even with all his fine publications, he will be lucky to make it out of Michigan. Sad! And peace begins with feeling your enemy’s pain.